Image credit: “Desert Oasis” by Aomar Boum

In Dr. Brahim El Guabli’s Saharan Imaginations (AS.300.338) course, students study deserts from a different lens– one that recognizes the ecological, cultural, and environmental significance of desert spaces and pushes against the view that deserts are empty spaces devoid of life. The course is interdisciplinary and utilizes books, articles, and films to engage with content in a variety of ways and to demonstrate the different approaches and perspectives surrounding the study of deserts. Dr. El Guabli previously taught iterations of this course at Williams College as an Associate Professor of Arabic Studies. In his first semester at JHU, he has brought the course to the Homewood campus in what he calls its “most developed form.” This spring semester, Dr. El Guabli will teach Indigenous Ecologies: Thinking with Indigenous Worldviews (AS.300.412).

We sat down with Dr. El Guabli to learn more about Saharan Imaginations:

What can students expect to learn from this course?

“The point of this course is to bring attention to deserts as an environmental and a humanistic space where life exists and which lend themselves to critical questions,” says Dr. El Guabli. “Unlike what we usually think when we evoke the word “desert.”

Often, deserts are spaces associated with emptiness, drought, absence of life, and death. Dr. El Guabli designed Saharan Imaginations to reject and reframe these associations, and to demonstrate to students the value and liveliness of desert spaces.

“Deserts are harsh environmental spaces,” says Dr. El Guabli, “but they are not at all empty or devoid of human, animal, plant, or insect life.”

Rethinking what is lively, what life looks like, and how we approach life is the fundamental aspect of this course.”

Throughout the course and by analysis of different histories and media, students learn about the ways that deserts have been both valued and exploited in the past. Students study exploitative histories of desert colonialism, sexual and spiritual fantasies, nuclear testing and disposal, extractivism, chemical and military experimentation, and incarceration. Such histories demonstrate the ways in which deserts have been dismissed and weaponized in the past due to their portrayal as empty spaces. Saharan Imaginations dismantles this construction and offers students the tools to reimagine not only their perceptions of desert life, but to reimagine perceptions of life in general.

“Rethinking what is lively, what life looks like, and how we approach life is the fundamental aspect of this course,” says Dr. El Guabli. “[The course helps] people think in ways that value different types of life and to question the ways in which we are taught to value certain manifestations of life over others.”

How does the course content intersect with environmentalism?

As humans, we consider an environment important if it is useful and lively, says Dr. El Guabli.

“Useful means that we can make it into something that serves human needs,” he says. “Once a space is constructed and envisioned as being useful for humans, it becomes a place.”

Deserts, he says, have been viewed by most humans throughout time as “good-for-nothing” spaces– not places. As such, humans have either transformed them into “good-for-something” spaces (farmland or development), or have continued to treat them as “good-for-nothing” spaces used to host destructive and undesirable human creations.

Instead of trying to project our perceptions of life onto desert spaces, we have to think about them as their own ecosystems.”

“Once we consider something important, we take measures that protect and prescribe how we treat it and that prevent the behaviors or actions that can mistreat it,” says Dr. El Guabli. Since deserts are often discounted as unimportant, few measures are taken to protect them.

“Instead of trying to project our perceptions of life onto desert spaces, we have to think about them as their own ecosystems, as their own organic environmental worlds that have their own richness and environmental autonomy.”

What motivated you to teach this class?

Dr. El Guabli grew up in Morocco in a dry region with little rainfall.

“My environment has never been empty,” he says. “It is always full of people and creatures, although it is a desert.”

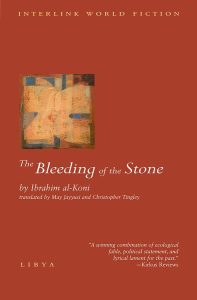

His primary influence, however, was Libyan writer Ibrāhīm al-Kōnī, a primary Arabic desert writer. al-Kōnī has written over 100 novels that take place in the desert, and his works inspired Dr. El Guabli’s research, the Saharan Imaginations course, and his own writing.

“al-Kōnī says that the challenge is to show that the novel is not about space, but it is about human beings,” says Dr. El Guabli. “For him, the desert is about the relationship between humans and their environment.”

What has surprised you most about this course?

Dr. El Guabli has taught the Saharan Imaginations course four times. Each time, he says, it becomes more complicated, deeper, and takes different approaches to the readings and materials.

“Through the years, what I’ve discovered teaching this course is that a lot of students come to it not understanding what it is going to be about,” says Dr. El Guabli. “Almost all of them finish it and say that they are surprised that deserts can be an entryway into theory, literary criticism, and environmentalism.”

The Saharan Imaginations course grew from Dr. El Guabli’s personal interest in the topic. This interest has continued to grow, and has become the subject for a book that he is in the process of publishing next year.

What broader themes as they relate to sustainability do you hope that students take away from the course?

Dr. El Guabli refers to “The Bleeding of the Stone” by Ibrāhīm al-Kōnī as a model for the intersection of sustainability and the desert. One of the most prominent themes of the novel surrounds the balance between human self-sufficiency and excess in relationship to the environment. The novel emphasizes the importance of a balance between human needs, animal needs, and the sustenance of the environment’s self-renewal.

“Nature has its way to balance itself, but wisdom requires humans to be the ones who monitor this balance,” says Dr. El Guabli.

Another theme that “The Bleeding of the Stone” develops and that Dr. El Guabli incorporates throughout the course is the concept of “the unity of creatures.”

Human survival is contingent on the survival of other creatures with whom we share our environment.”

“The unity of creatures is this deeply philosophical concept that makes human life contingent on the life of other creatures,” he says. “People grow up thinking that humans are the center of everything, but human intelligence and the enterprises ensuing from it can be deadly if humanity does not take into consideration the fact that human survival is contingent on the survival of other creatures with whom we share our environment. This is the fundamental rule of the unity of creatures.”